The Imitation Game

Some of the world’s most brilliant people are also the most tortured. By existing on a different mental plane, they often sacrifice the social skills necessary to convey that brilliance and torture. The side effects produce the sobering, if not inevitable, conceits of The Imitation Game, a film placed so lightly into the biopic presser that it rarely shows its griddle marks. That’s largely because of its subject matter, Alan Turing, the British mathematician who broke the Nazi Enigma Code during World War II. His machine, which solved the German’s secretive communication puzzle, eventually saved millions of the Allies and prevented war from continuing another two years. He was never treated like a war hero.

Turing, along with the other linguists and coders recruited to England’s Bletchley Park, took an oath of secrecy about their work after the war ended. It was meant to cover up the operation but it becomes something devastating. Besides being socially awkward and somewhere on the autism scale, Turing was also a homosexual. Thus, in his lifetime, he was closeted twice. It’s an easy metaphor for director Morten Tyldum but it’s also painful because of its grim reality. When you first see Turing, inhabited intensely by Benedict Cumberbatch, he’s near the end of his short life, with his biggest achievement collecting dust in a messy apartment. In the periphery, an English detective is looking for indicting evidence about his communist leanings until he finds the more damning material. His hidden heroism was lost to Cold War paranoia and homophobia, to draconian laws and chemical castration. Beginning at the end seems to be the rule with British biographies now, at least since Meryl Streep started The Iron Lady as The Wrinkled Lady.

The interrogation is an expository device to rundown his list of achievements, which are compressed into two earlier time periods. As a child he’s seen fascinated with cryptography and with another boy, Christopher, whom he will name his machine after. Years later when he has grown into a mathematician and crossword champion his skills aren’t scolded but recruited. When Commander Denniston, a military general in charge of Bletchley, begins lecturing him about using pencils and paper to race against the clock it’s as though he were vying for the typewriter as a contemporary device. Turing knew the answer to testing 20 million settings in 20 minutes wouldn’t be fit for the brain. His retro “computer,” which took months to create, was criticized and bullied early on just as much as it was ultimately praised.

Turing’s colleagues, the brightest played by Matthew Goode, are frustratingly forced to undertake his mechanical plans but their compatibility is shaken on a human level. Turing can’t connect in a relational way. Their sarcasm plays as serious. General questions get highly literal answers. It’s when he meets Joan Clark (Keira Knightley)– the only woman on the coding team– that he finds someone to share in his misery. She naturally becomes a love interest but she also provides the film’s warmest scenes.

Clark provides a new window to empathize and understand the side effects of Turing’s genius. And yet she is equally problematic. Tyldum, like the movie, is too shy to show Turing actually being a homosexual. Clark is clearly the brightest of all the men but her gender becomes a problem for her parents, who want her home and married. The only way Turing keeps her on the team is by proposing to her. You’re asked to believe, like the stealthy MI6 agent played by Mark Strong, in Turing’s conflation of sexual obscurity and idiosyncratic mental capacity. You only witness the latter.

Tyldum isn’t really able to demonstrate all of these components. Part of making a film like this is about accessibility, stroking the emotional chords without burying them beneath the math and tedium of waiting for “eureka!” But Tyldum, with screenwriter Graham Moore, still makes the group project insular and exciting in its countdown. Brief images of the war provide context but the drama is focused solely on Christopher, its churning matching the humming of tanks hundreds of miles away. That audible cohesion suggests both are weapons just operating in completely different environments.

The scenes at Bletchley, specifically in the barn where Turing configures Christopher, play as a contemporary Silicon Valley. Some 70 years later “Hut 8” has transformed into sprawling acres of Facebook and Google headquarters. When Denniston barks at Turing about following the “chain of command”, you realize how backwards his methodology is just by virtue of our digital democracy. “Can machines think?” the detective asks Turing later in the film. The question is asked seriously, even frighteningly, masking as a question about homosexuals. “They think differently” Turing responds. It’s like explaining something to a child who keeps asking “Why?” but doesn’t really care about the answer. The adult just wants to go back to work. The tragedy is that Turing wasn’t allowed.

4/5

The Hunger Games: Mockingjay — Part One

War is just about to begin in the latest Hunger Games. Instead of stealing codes though, hackers are breaching invisible security shields and infiltrating television broadcasts. This young adult series has thrived on juxtaposition, creating contemporary technology to excavate historical injustice. It’s going for something timeless in the way that all revolutions emerge from spontaneous protests. That’s what’s happening here in this third of four movies being adapted from Suzanne Collins’ trilogy of books. The proletariat is restless and ripe; they just need their poster boy.

That would be Katniss Everdeen (Jennifer Lawrence). But she’s not a boy, a simple fact that has made this series about more than just the slow overthrow of a dictatorship. Maybe it’s silly that four movies are being made when three would suffice. But splitting Mockingjay into two adds at least one more statistical blip to balance out the testosterone that takes up more than three quarters of screens each year. Katniss can play ball, too. When you watch her hunt, or aim her arrows at something more explosive, there’s a partial thrill in seeing a woman unleash a skill that has been codified as male (arrows penetrate, after all). The beleaguered districts are looking for inspiration. “They’ll either want to kiss you, kill you, or be you,” someone tells Katniss. She’s a perfect fit.

Mockingjay doesn’t require you to know the previous movies because its symbolism and story is sharp and straightforward. The previous tension has carried over. In the backstory, an Appalachian dystopia called Panem consists of 13 districts run by a totalitarian government under President Snow (Donald Sutherland). After the districts failed to overthrow the Capitol, Snow instated a Hunger Games, a sadistic reality show in which two members from each district are pitted to kill each other until one remains. Katniss and Peeta (Josh Hutcherson) have survived two of these bloody competitions. The remaining insurgents and citizens are bunkered into District 13, strategizing their next uprising.

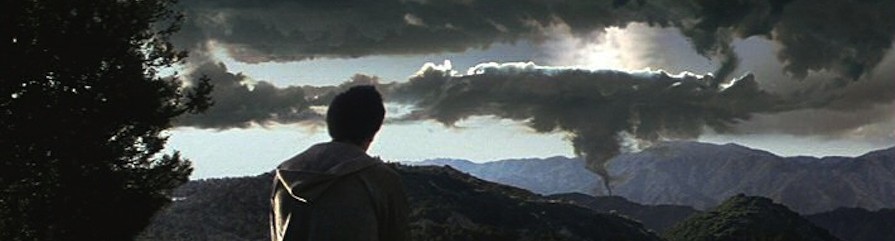

Part of what made Catching Fire such a significant sequel was its understatement. It didn’t need to broadcast teenagers at war to be captivating. This movie carries a similar tone, stern and ambitious. The story hinges on making propaganda for the masses, using Katniss to spark an advertisement to solidify a unified army. At first she is unwilling, especially when she realizes Peeta has been captured by Snow. Like any hero, she needs context to rekindle the reason she’s fighting. She goes back to the rubble of her hometown in District 12, now skeletons beneath rock the government has repeatedly bombed. This is Simba returning to pride Rock after Scar has famished the land. The visual aid obscures her pleasant memories. It’s also liberating. Now, there’s nothing to lose.

The joys of these movies are watching seasoned actors treat small parts with integrity. Francis Lawrence, in his second time directing, steals a brilliant performance from Phillip Seymour Hoffman alongside Jeffrey Wright, Woody Harrelson, Elizabeth Banks and Julianne More, the reserved leader of District 13. You never get the impression this is just a paycheck for them, or that it’s beneath them. The imagery of Nazism and slavery keep this science fiction weighted to the realities of humanity’s regretful past. The rubble stands in for natural disaster. It remains familiar even amongst industrialized, miles-long bunkers and spaceships dropping warheads.

Jenifer Lawrence continues to convey a young woman so tethered to family that she struggles in the same myopic worldview. The propaganda videos are a way to snap her out of it. Originally she stands in a studio in front of green screen technology and is asked to read from a script. It goes horribly wrong. Her believability is on the battlefield where emotions are raw and yelling into cameras, held by a small tagalong crew, seems rational. After repeating this several times, it soon becomes wearisome.

Part of the problem in splitting up a final chapter is knowing where to split it up. The ending of Catching Fire was brilliant because it grabbed Lawrence’s facial skills and packaged them into a killer last shot. (Director) Lawrence uses a recovery mission to end Part One that features Gayle (Liam Hemsworth), Katniss’ moony lover, and a team of other male soldiers. Katniss just stands there watching the screen. It’s the first climax in this series where she isn’t doing anything. Lawrence returns to Katniss for the final shot, but this time her features coopted by a glass wall, softening the image. The intensity ending Catching Fire has been dampened by trying to replicate it. Instead of being inspired, you leave feeling teased.

3.5/5

Rosewater

Rosewater is a good, altruistic, small movie. It’s John Stewart’s directorial debut and thus it exists, like The Daily Show, as something satirical to point out something largely overlooked and disregarded. It follows the true story of Iranian-born, Canadian Newsweek reporter Maziar Bahari, who was imprisoned into solitary confinement for several months by the Iranian government while covering the country’s 2009 controversial election. The film follows his return to Iran to interview challenger Mir-Hossein Moussavi battling the incumbent President Mahmoud Ahmadenijad. The latter’s victory sparked outcry from many citizens protesting the legitimacy of the voting process.

Bahari, played passionately by Gael Garcia Bernal, gets swept into the riots, filming everything with his camcorder. It’s not until he agrees to an interview with The Daily Show’s Jason Jones– pretending to be a U.S. spy– that he gets into trouble. Iranian authorities snatch Bahari from his home and interrogate him. “Why were you speaking with an American spy?” asks a man named Javadi (Kim Bodnia), tasked with forcing out answers. First you laugh and then you cringe as he replays the The Daily Show clip. They actually believe the segment was real. Bahari’s bemused bewilderment transforms into a blindfolded one.

You sense in some ways Stewart feeling slightly indebted to making this film then. It’s a solid first effort. He straps cameras beside a motorcycle to give you the sprawling mosaic of Iran’s crowded streets and mural art. He uses concrete walls and projects background images and info-graphics onto them for a unique touch. It’s juxtaposed with Bahari’s lonely fate, living day by day in a cell that’s just a few feet wide, acquiring visions from his father and sister. In some angles the room feels large, especially when Javadi, whose cologne’s scent the movie is named after, walks in. Stewart isn’t trying to make this black and white. Javadi has a family and his job is to torture. It’s not a sadistic practice or hobby. This is his livelihood.

Bernal makes this movie, especially once his character learns his torture is really a game. He figures out how to amuse himself to stay sane. He comes up with ridiculous stories for Javadi. At one point, after getting to speak to his wife over the phone, Javadi hangs it up and pushes him away. Bernal looks like he’s crying in pain until he changes sobs into laughs. Or was he laughing all along?

Stewart is sometimes a little heavy handed with his imagery, including a scene near the end involving an airline passenger. But he also knows how important imagery can be, and is, to his story. Rosewater is about a government that doesn’t understand the flaws in their totalitarian, antiquated idea of censorship. For every satellite or news journalist they beat down, ten more spring up. They’re fixing a dam by plugging its holes with gum. Stewart’s movie suggests that the water will continue to leak no matter how many pieces they chew.

3.5/5