Very early on in Chappie, Sigourney Weaver, playing the head of a private defense company, shoots down funding a robot that can recite poetry and paint pictures. It’s a brutal setback for its proposing inventor and engineer, Deon (Dev Patel), who has been in his basement for years figuring out how to create a machine that thinks and feels like humans. It’s too bad considering he’s already created everything she needs, a robotic police force called scouts that have revolutionized government authority. Well-equipped and programmed to crack down on rampant crime, the scouts enforce the law upon the countless, anarchist thugs roaming Johannesburg. What’s the need for artsy-fartsies in a desolate landscape?

This movie takes place in the near future because Anderson Cooper tells us so. It’s one of those movies that rely on a lot of expository dialogue – from newspersons to actual characters — to describe everything we can already clearly see. That opening rejection of a potentially creative technological achievement feels microcosmic of this movie, a good idea shot down by lots of bad ones. Neil Blompkamp is in charge of the socially splintered and restless South African circus again, but unlike District 9, he has trouble being ringmaster. Writing the script with his wife, Terri Tatchell, Blomkamp doesn’t provide so much a vision as just visuals. He’s created something inspired, not necessarily something inspiring.

The sci-fi derivations he’s borrowing become exceedingly clear once that robotic police force is introduced firing weapons and watching bullets bounce off their armored suits. They’re even clearer when Hugh Jackman shows up pitching Weaver a bigger, human-controlled weapon – operated with a Professor X-like helmet — that looks like the exact replica of Robocop’s ED-209. This also gets shot down, understandably, because its purpose seems only legitimate during war. Deon, meanwhile, stares at a motivational sign in his cubicle and refuses to let his boss halt the future. A late night chugging Red Bull and a stolen power chip brings his sentient to life. He just needs a decommissioned body as its vehicle so Frankenstein can create his monster.

But this new creation is hardly a monster, at least to start. A trio of thugs, two named Ninja and Yo-Landi, playing versions of themselves, enter the plot with a serious debt to pay. They hijack Deon’s van hoping to switch his robot into a criminal abettor for a heist they’re planning. Instead of nurturing his project in a friendly environment, Deon, with a rifle pointed towards him, submits to this group of pale-skinned bad haircuts to raising him in their abandoned factory. You quickly realize the rest of the movie is going to focus on this random group of actors, teaching Chappie, which Yo-Landi names, to be a criminal before he even knows the alphabet.

Some of this is comical but highly disconcerting, like the way Ninja teaches him to cock his gun sideways, strut around bowlegged and wear chains around his neck. A few neon tattoos later and Chappie, voiced by Sharlto Copely, has learned to walk like a gangsta and speak like one, too. “Good boy, Chappie,” they tell him, treating him like a dog that they closely resemble. All of this leaves little room for Weaver or Jackman, sporting a mullet and tight shorts, to be of importance. It’s easier to turn them into one-dimensional villains but it’s also a wasteful decision.

Sometimes movies get so preoccupied with a few characters getting from point A to point B that their surroundings lose all comprehension. Chappie suffers from this general principle. Usually plot holes in science fiction can be smoothed over with enough compelling drama and plausible, diverting action sequences. The problem here is that questions keep popping up. What are the workers in this company’s cubicles actually doing? Why is there no security checking Jackman’s devious character in the building at night? Why is everyone living in Johannesburg a criminal, white-collar suburbanite, or government employee?

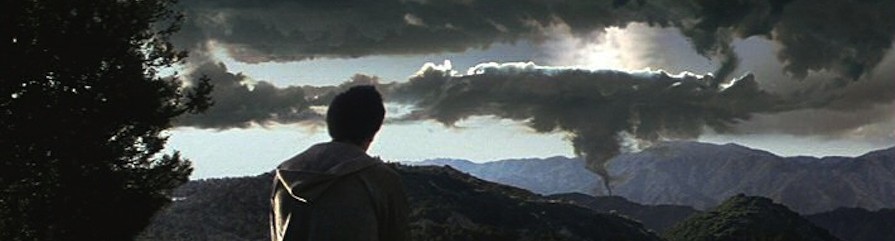

You’ve come to expect a lot of questions to be asked in Blomkamp’s movies. Answers are rarely attempted. While Elysium didn’t make much sense, you could see it struggling with class structure and racial politics. If Chappie completes Blomkamp’s triptych of segregationist injustice, it offers little new direction or excavation. Just look to Blomkamp’s rousing finale, which trades in examining poverty and the moral possibilities of Chappie — his existence, his functioning, his future — for a fiery shootout (by a warehouse, of course) that tries to make martyrs out of the robot’s kidnappers.

At one point, Yo-Landi tucks Chappie into bed and reads him a storybook called “Black Sheep.” The message is overt, and feels a tad false, but it also carries a warmth that the movie fails to keep chasing. Maybe I’m not giving Blomkamp enough credit in that regard. He’s made the opposite of iRobot. He’s made humans so despicable that Chappie, a robot we’ve only just come to understand, take seriously and possibly care about, seems like he’s the best replacement for humanity.

2/5

One of the several climaxes that push Run All Night towards its beleaguered finish also takes place beside old warehouses, specifically on some crowded train tracks. At this point, Liam Neeson, a weary hit man named Jimmy Conlon, is chasing down Ed Harris, playing Jimmy’s former boss and best friend Shawn Maguire. After wading through 90 minutes of grim deaths and chase sequences, watching two old Irish men dodge behind train cars and hobble into a barely visible shootout doesn’t feel like proper punctuation. It’s a question mark in a long line of exclamations.

That’s not to say Neeson can’t keep carrying a film like this. Since Taken, he’s become the most reliable action hero bottling up revenge and paternal masculinity and uncorking it upon international terrorists, mobsters and anyone else that threatens his family or democracy or whatever else the script believes important. Maybe it’s the character he’s playing here — a tired drunk with a long list of murders and regrets to his conscience — but Run All Night is the first time the lines on his face start showing his age. Neeson has recently admitted he only has one or two more years left playing these kinds of roles. He’s made five movies in just the last year. You can’t blame him for slowing down.

The bloody mess this time is constrained to about 16 hours. Shawn, once a big-shot drug boss, has decided to be stingy with his son, Danny (Boyd Holbrook), after he offers his father a chance to do business with two Albanians and shipments of heroin. Shawn refuses the offer – he’s seen too many people die from a good drug – but doesn’t realize the trouble he’s started for his son. Later that night the Albanians demand their money and corner Danny in his living room. He responds by popping bullets into both of them. One staggers down the stairs and into the street before Danny finishes him.

Jimmy’s son, Mike (Joel Kinnaman), unfortunately sees all this from the limousine he drives, along with Curtis, a teenage black kid – capturing the murder on his smartphone — that Mike has been mentoring at a local Queens boxing gym. Danny, wanting to tie up loose ends, goes after Mike, who subsequently has cut Jimmy out of his life. Jimmy’s been a bad father, killing men and the relationships in his life. It’s a detail that gets confusing when he ends up shooting Danny dead and saving Mike’s life. Soon, Shawn is sending out his squad of henchmen after the both of them in some bizarrely sowed seeds of vengeance.

Harris probably knew what he was getting into here but you can’t help but feel bad for him. He’s trying to make something out of the nothing he’s been given. I was trying to think of a real explanation as to why he’d really want his best friend’s kid dead. It never came. I’m guessing writer Brad Inglesby couldn’t really tell you either. He seems to be relying on his director, Jaume Collet-Serra, to shoot enough slender havoc that the reasoning behind the gun shooting and the car chases underneath the elevated subways gets lost within its own noise and the dozens of near fatal escapes.

To his credit, Collet-Serra, the Spaniard who seems to be making a living off Neeson (he directed the boring Unknown and last year’s exciting, contained thriller Nonstop), keeps the action tight and unending. Some if it is gimmicky, like some bad CGI lightning strikes, but some of it works, like the Google Earth camera that bounces between different addresses. Usually, there’s a moment in these types of movies I start thinking about the massive amounts of collateral damage a city has just inherited, how many shattered lives and emotional meltdowns a minor wrong turn from Neeson has just produced. Maybe because this is New York City (we’re reminded about every ten minutes with some sort of helicopter shot), but my mind never had time to wander.

That’s partly because by the time Common shows up as a high-tech hit man in a large, mostly black tenement building, the movie has admitted it’s not worried about any semblance of reality. These scenes provide some more admirable chases, this time between stairwells and fire escapes. Mike and Jimmy are there to find Curtis, to get his phone to show the police the situation. Vincent D’Onofrio plays the beleaguered detective aiming to finally nab Jimmy but his team, which has already taken a beating, keeps walking into Conlon family landmines.

Amidst all of this, Mike’s wife (Genesis Rodriguez) and two daughters are whisked away upstate. This is a movie about fathers but it’s one that only cares about them in relation to sons. It keeps coming back to a picture of Jimmy with Mike as a boy, a way to soften the blows you’ve just seen the older guy deliver. That’s Neeson’s lasting power. He makes you leave the theater thinking he’s a good guy when everything he’s just done has suggested the opposite.

2/5